Context in social science education Reflections on contextualization in civics and critical citizenship

Introduction Education is a social enterprise. It is deeply rooted in social reality. Even though the biological constitution of a human being is the same across the world, social reality differs hugely. Human beings across the world have different clothes and eating habits. They also have different religious beliefs, forms of government and even different […]

Introduction

Education is a social enterprise. It is deeply rooted in social reality. Even though the biological constitution of a human being is the same across the world, social reality differs hugely.

Human beings across the world have different clothes and eating habits. They also have different religious beliefs, forms of government and even different moralities.

Yet humans try to find some commonality, and some pattern among all this variety. We have tried to formulate concepts to describe and understand this commonality, through generalizations.

However, these generalizations and concepts are not always available to children at a young age. Concretization and contextualization are two pedagogical strategies through which these can be made available.

I will be sharing my reflections on our experiences of the above in a social science education and primary education program. We had developed this at Eklavya in Madhya Pradesh. This was a program that worked closely with and for the government school system. It also helped other states develop pedagogic material in their own contexts. My experiences, which form the basis of these reflections, span nearly 40 years.

The background of the Social Science Program

Eklavya’s Social Science Program was developed between 1982 and 1995. It was being run in eight government middle schools of Madhya Pradesh’s Hoshangabad, Bhopal and Dewas districts. The program was run in partnership with, and with the permission of, the Government of Madhya Pradesh.

Social Science, at that time, was considered the most boring subject of middle school. We began with the question of making the subject more meaningful for children. This took us to the basic questions of why social sciences, why history, why geography, why civics?

We debated at length on the integration of the social sciences. Some of us saw it as one comprehensive subject. However, we finally decided to retain the structure of history, geography and civics for various reasons.

History and geography were structured around the basic concepts of time and space respectively. The basic question that we tried to address through civics was this – “What kind of education would make a critical and constructive citizen?”

Civics is a subject that has traditionally drawn from many social science disciplines like political science, sociology and economics. It was redesigned as critical citizenship. The name remained civics though. A change in name may not have been agreed upon by the government. The experimentation had been allowed under the existing curricular framework.

This brought us to many of the following elements of content and pedagogy. A basic knowledge and critical understanding of the economy and how it works is important. This gives an idea of the issues that need to be addressed by policy, so as to assess the functioning of a democratic government.

A basic knowledge and critical understanding of political institutions and processes is also crucial. A similar grounding in social structure, and its interplays with economic and political life, was also seen as foundational.

It was also felt that students need insights into laws and policies. The critical role of an active citizenry in bringing to light anomalies in their implementation and in developing alternatives was also seen as fundamental.

The need for contextualization and concretization

There are some commonalities, patterns and concepts that form a major part of the content of civics at the middle school level. Their very nature is abstract. Concretization and contextualization are two ways in which abstractions can be made more understandable.

We reviewed the middle school textbooks. This process showed that the presentation of concepts in the textbooks of classes 6, 7 and 8 was dense. It did not explain any of the concepts or sub-concepts in a meaningful manner.

According to research in children’s cognitive development undertaken by Jean Piaget, children of upper primary and middle school are at the concrete operational stage of thinking. According to this formulation, this is true of children at the high school level as well. This means that they are just beginning to make logical sense of experiential reality. Hence, it is not easy for them to understand abstract concepts unless these are related to their manifestations in the reality around them.

In pursuance of the question – how would children of class 6, 7 and 8 understand these concepts and ideas, we read and discussed them with children of class 6. The idea of a state and its capital were discussed, as were panchayats.

Children were used to memorizing names of capitals. Yet they were clueless about what really is a capital city. That it is the city which houses the headquarters of government, where decisions for the whole State are made, went totally above their heads.

They knew a few facts about some capital cities like Bhopal and Delhi, such as having big markets or a large lake. They tended to ascribe these attributes to all capitals. They seemed to be clinging on to some concrete information and putting it into the definition of a capital!

It was clear from the above experiences, that it is important for children of middle school age to have specific and concrete manifestations of the concepts that are being talked about. The examples need to have details of specificity. These also need to be chosen carefully. These concrete examples must not be random stories. Rather, these must be chosen to illustrate specific aspects of the concept.

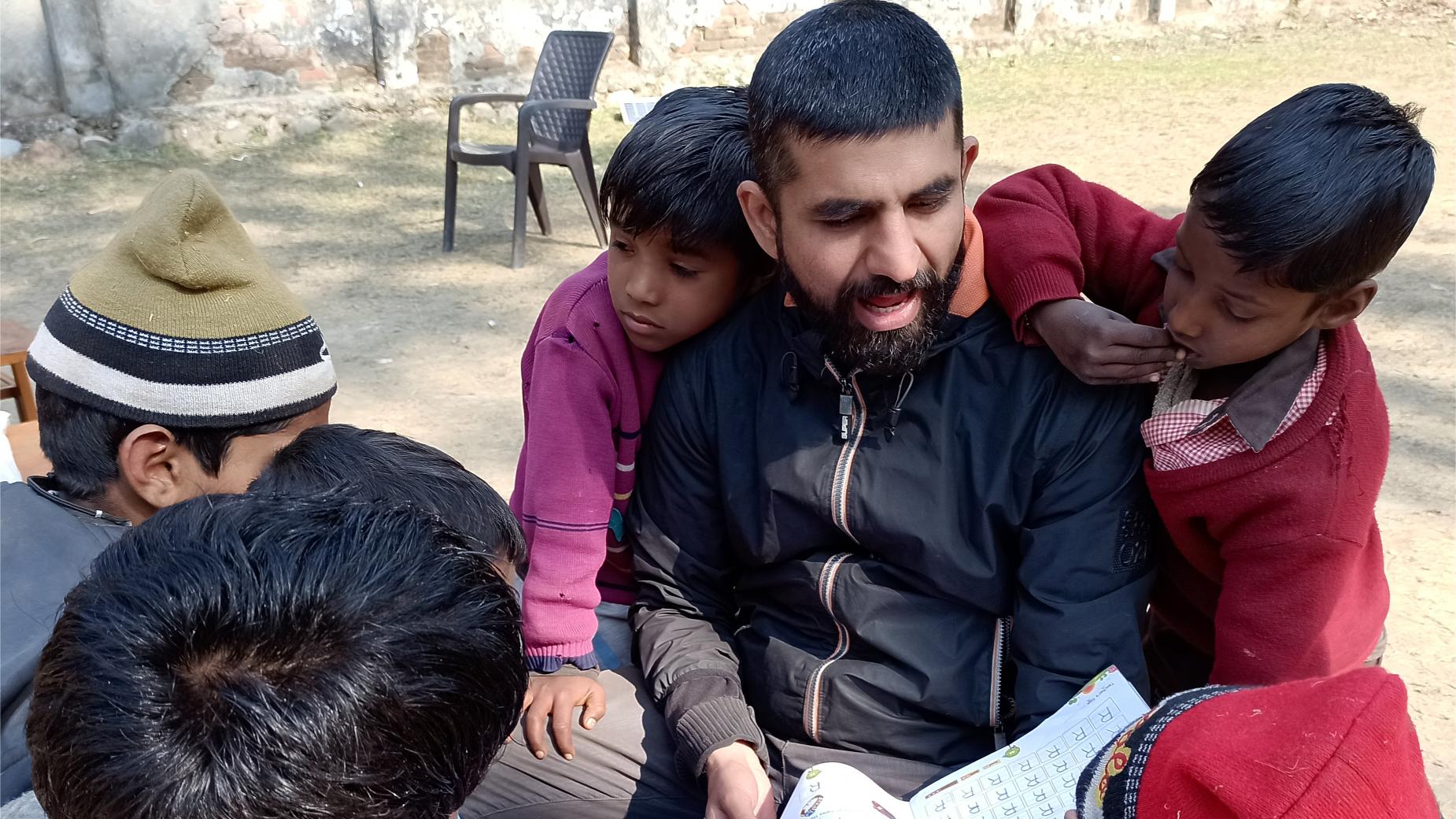

Such experiences made us think of concretizing the content of the chapters, and building on the children’s own experiences. We asked children questions about their experiences. For example, we discussed with them their experiences about their own panchayats. Who is the member and the sarpanch? When was the last meeting held, etc.

We also asked them questions about their agricultural practices, their landholdings, about what the parents do, what their profession is, etc. Often such queries touched upon sensitive issues of caste and village politics. We also found to our surprise, that the children of this age group had very little interest in talking about their experience’s ab initio.

Another issue that came up was that the reality of the political institutions was such that in practice there was very little happening. For example, panchayats had not been constituted. Meetings were hardly being held. This gave a very cynical view of democratic functioning.

We received the following feedback from an SCERT personnel, when we showed them these draft chapters – “Do you want to raise children believing in democracy or being cynical of it.” Our objective was obviously the former.

We seemed to have got stuck between abstractions and not being able to build positive understanding of democracy and active citizenship based on experiences from below. Luckily, through our reading and research, we found that there were many instances of collective citizen’s initiatives for implementing the provisions enshrined in the constitution. We used these as concrete examples in contexts to build understanding of democracy in practice.

A third issue came up when we tried to help the children explore their own environment, see patterns, and generalize in primary school. For example, they were asked to reflect on questions like – “What are the main features of houses?” “What are the materials with which these are constructed?” “What are the patterns?” This approach didn’t seem to work. As often, the immediate environment didn’t spark much interest. It was too taken for granted.

We discussed the issues shared above in detail. This brought up the idea that instead of building on the local experiences of the children in the class, where we faced limitations and bottlenecks, the writing team would research and write either true narratives or material based on fact-based research.

We also decided to follow Jerome Bruner’s approach on the basis of which he developed the much-acclaimed course “Man: A Course of Study (MACOS)”. Three organizing questions had formed the basis of this course. These are shared here.

What makes man human and distinct from other living beings? How did we get to be that way? How can we become more human(e)?

The course was woven around language tools and social organization. Its core content dealt with the lives of the Netsilk Eskimos.

Taking a cue from this, we introduced some chapters from esoteric contexts like the Arctic, and the Equatorial forests, etc., to contrast with the children’s own lives. It worked to an extent in primary schools. For middle school, we took a relatively linear approach of closer to home for class 6, the state level for class seven, and the national level for class eight. The state curriculum being organized that way was also helpful.

Contextualization and concretization

Concretization is an illustration of a concept. For example, let us say one is talking of representational democracy or forms of production, or, for that matter, economic value. A specific example in which these concepts manifest themselves, e.g., for representational democracy, the constitution, and the functioning of a panchayat or a state or the central government is narrated first. The context of the concrete example is made abundantly clear. The concept is discussed after this has been done. Similarly, for forms of production or value.

As mentioned earlier, social reality differs a lot over both time periods and across geographies. A variety of examples were taken from different contexts to drive home that there is no one reality but a variety of realities, and that the differences and commonalities depend on the context. The contextual details of each example are important. These include when something happened, where it happened, and who did what. The variety of contextual, concrete examples are then compared with the conceptual parameters, e.g., representation, process, resolution of differences, etc. The comparisons help generalize to abstraction the underlying concepts of a theme, e.g., the fact that democracy is based on equality, participation, freedom, fraternity and accountability.

The most important issue we dealt with related to selecting the themes for the narratives. In internal team discussions, we grilled each other with questions and critiques about each other’s work. We talked to university professors of relevant subjects, including politics, economics, sociology and law for the section on civics, history and geography. In the process, we clarified the conceptual frameworks for the content of the proposed chapters for ourselves.

Secondly, as far as possible, the content was attempted to be made specific enough for children at this age to comprehend. Most were at the pre-operational stage. Some of the children were at the concrete operations stage, at the latter end of the spectrum.

Thirdly, the aspects being talked about would need to be familiar to children. These would be concretized narratives with specific manifestations of relevant concepts and themes from different contexts. These would try to evoke an image of an idea, an event, or a phenomenon, complete with active people populating the narrative.

I will try to clarify the issues shared above with examples from civics or critical citizenship. This is the section I, along with a colleague, formulated and wrote up.

To write up the above, we researched at two different levels. The first were the localities. The second level was that of the area of enquiry at a broader level. The attempt was to find out the ways in which the concepts manifested themselves in the area around the children. We also wanted the children to develop an understanding of how these were theorized in the area of enquiry. For example, production, exchange and value were three very important concepts in the understanding of economic life. These form the basis of understanding economic policy and its effects.

To develop the contextualized narrative, we went to the nearby haat and mandi. We talked to people who were sellers and buyers. We observed these markets for a couple of days. We also read up on the research on haats and mandis, even if these happened in other geographies – in Himachal or in Tamil Nadu. We wrote up the whole issue of exchange based on the above research.

Similarly, we researched agriculture and industry. We developed the framework based on the forms of production paradigm. The goal was to understand industry and the categories of farmers and labourers. We also tried to show how these social groups are affected by different aspects influencing agriculture. These factors include technological and biological advances, such as green revolution or agricultural policies.

This approach was quite different from the focus on demand and supply based micro/ macro economics, which forms the basis of most high school and undergraduate courses.

We chose these paradigms for the following reasons. We felt these are easier to exemplify and concretize into narratives that children could understand and relate to. We also thought that these brought out more meaningful learnings for real life analysis.

Thus were born the chapters on the small, big and marginal farmers and landless labourers and on the transition from self-owned production to putting out to large industry, as well as on markets, for classes 6th and 7th. The policy chapters for class 8th and the chapters on the constitution and government were based more on secondary research and newspaper articles.

A process of discussion was included in each chapter. In these, the thought process moves toward abstraction and concept formation through patterns and qualified generalizations.

Contextualization, representation and perspective

When we include a contextualized, concrete example to explicate a concept, we must make many choices. These depend on whether the material is for a school or a set of schools, or for a State or the nation.

Where and when is the example from? If it is for a set of schools, then is it from the vicinity? If for a State – is it from the State – then which part of the state is it from? If for the nation, where from? Is it from now, or a few years ago, or a few decades ago? Who are the characters? Whose voice is prominent? What is it saying?

As the textbooks we made were used in eight (8) schools across three districts and four (4) blocks, our examples for the economic chapters on agriculture, industry and markets were from the area. The children’s own experiences could be very like those in the case study example or a bit different.

Expression of their point of view is very important to the students’ conceptualization. Asking the children to discuss aspects of the examples, and to articulate their viewpoints, is a strategy that we used throughout.

We tried to build in a perspective where marginalized communities’ voices would be represented. We also built in examples of positive changes in response to people’s collective voices. These ranged from narratives about local bodies, exemplifying the process of enforcement of fundamental rights with actual cases, to examples of debates during the making of the constitution.

Contextualization in state and national level textbooks

We were asked to help in creating such contextualized books for other States and for Ladakh. The latter was the only district that had district-level textbooks at the primary level. An important issue here was how to select contexts that would be familiar to all the children over a larger area. A process of selection of the examples from the geography that illustrate the concepts and the sub-concepts in the conceptual frame for the curriculum were picked up, researched and written up.

We also helped NCERT develop the national level textbooks. Here too concretizing and contextualization were used, including case study like chapters with live characters. These helped the children get a real feel of abstract concepts.

Contestations and challenges – by way of a conclusion

Contextualized concrete narratives have proved quite successful in creating a deeper understanding of abstract concepts of economics and political science. They have also helped in developing a deeper understanding of real conflicts and contrasts between ideals and reality. These have the power to make active citizens.

Because this power becomes evident, there is potential contestation and controversy by the educational establishment. This includes teachers, educational administrators and even many academicians.

This was one of the major reasons for the controversy over MACOS, over Eklavya’s curriculum programs, and the intermittent controversies about textbooks. There is, and always will be, resistance to attempts at education for a just world.

One must decide whether it is a worthwhile endeavour. If so, controversies and challenges are a part of the game. Be that as it may, it is a powerful way too – reading the world, in order to change it.

No real and meaningful attempt at good social science education can be made without the purpose of creating active citizens for a just and democratic society. The risks are an occupational hazard that need to be mitigated with a robust strategy.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!