Dialogues between the contextual and the general: can we teach against casteism?

In this short article, I explore the strange trajectory of the role of context in learning. I illustrate this by what it might mean in teaching about a theme like casteism.

In this short article, I explore the strange trajectory of the role of context in learning. I illustrate this by what it might mean in teaching about a theme like casteism.

More and more educationists are saying that children learn best when teaching connects with the world around them. This is not a new idea. John Dewey, for instance, said that all humans learn by coming to grips with their environment and trying to make sense of that experience.

Children form concepts and schemas when they play with things and ideas around them. They develop attitudes and emotions which motivate their actions. The teacher’s job is to create the conditions in which children may want to learn and to support their growth.

Learning was contextual for most of human history. Children in hunting-gathering bands learned where the juiciest berries were found in the jungles surrounding them. They did not learn general theories of plants and nutrition. Children throughout history learned more by observation and imitation of what was going on around them than by formal instruction into ideas and theories which came from far away.

Until recently, the classroom and its daily, regular learning of abstractions was only for a few. Those few learned in the classroom what could not be taught from observation or imitation of actions around them. For instance, they might be instructed directly by a guru about a philosophy of deeper ideas and narratives, which were far removed from their everyday world. Thus, they might learn about the Vedas and the Upanishads and that abstract entity which was not in this thing or that but was beyond all of it. Such abstracted learning made up a small part of all that was being learned in that community and initially dealt mainly with metaphysical topics.

Gradually, other kinds of non-contextual knowledge and teaching, like that of mathematics and theories about the material world seem to have emerged. However, this teaching was still limited to small numbers and a few institutions. These were dedicated to the teaching and learning of what could not be learned from the family and the neighbourhood.

In other words, these institutions necessarily taught about something which was remote from the students’ immediate context. The family and neighbourhood took care of the rest. The farmer’s children learned when to sow seeds and how to clear fields of weeds. Girls learned from their mothers about how to cook and boys learned how to plough the land. In some societies, both boys and girls learned the same things.

Universalistic institutions redefine contexts

The rapid rise of formal schools and classrooms which took place over the last three centuries has moved the idea of what is worth learning further away from the immediate into a broader field. Children learn biology and not how to sow jowar and bajra. They learn loyalty to the nation and not to their caste or tribe.

Knowledge is now seen in a more de-contextual or universalistic way. It is important to note though, that it is never fully de-contextual. Schools and classrooms have taken students away from the actual community life and put them into a special, insulated space. And parents are usually quite happy about this. It’s because schools are seen as a ladder to another world, with the promise of greater status, power and wealth.

The biggest single jump toward such learning took place with the expansion of mass education after the 18th century CE. The Prussian state was one of the earliest to make a law that all children had to go to school and learn a knowledge that was specified by the state. What they learned in the school was no longer what they could learn from their families, neighbourhoods or workplaces.

Especially after the defeat of the Prussians by Napoleon in 1804, schools became a place to learn patriotic fervour and loyalty to the king who ruled in the far away capital. This was the knowledge which those in government thought that children should learn. It was quite removed from local loyalties and affections. This was not really a fully universal, de-contextual knowledge, as noted above. Instead, the context was now defined by broader institutions like the state and the nation.

The shift in school knowledge was a move away from the family, and local communities and their institutions. This was connected with basic changes in the nature of societies and particularly in the powers that decided what was considered worth learning.

In colonized India, for instance, the British shaped what the new context was. Children were sent to British instituted schools. This was because these were the main pathway to getting jobs in the government and also in the new economy that was emerging under colonial rule. The British insisted that their own syllabi and textbooks be carefully followed. They were deeply suspicious of what local teachers and communities might want to say to children.

The move away from the local into new, relatively broader contexts only accelerated in the 20th century. In this period school education for all became a widely accepted social norm in countries around the world. Schools and universities have spread into countries with little industrialization and where the state is barely recognized beyond the boundaries of the capital city. There too the context is being defined anew and now includes much more than just the family, community and neighbourhood.

Contextual learning pushes back

Over the last few decades, there has been a renewed interest in the contexts of learning. This has several sources. There are differences in what each of them means and wants.

To begin with, the anti-colonial struggle, with people like Gandhi, was staunchly opposed to British education. The British appeared to be preaching a knowledge that was universal, true everywhere and beneficial to everyone. Indian critics said that this was just not true. The British were teaching what appeared to be correct from their point of view. They were trying to present it as universally true.

Sometimes even the British themselves did not believe what they were teaching. For instance, they taught in India how we were too immature to be choosing our rulers. Meanwhile back home by the end of the 19th century they were saying just the opposite, viz., that all men (not women till the 1920s) should be voting to decide their rulers.

In short, the freedom struggle demanded that we Indians should decide what should be the content of our own education, and it should be designed according to our own perspective. For a while, this sentiment encouraged several Indians like Gandhi, Tagore and Aurobindo to think afresh about what our education should look like.

Gandhi, in particular, believed that Indian education should overcome the beliefs and practices of casteism. However, that sentiment slowly quietened down after independence. Indian elites began following global cues. They began to model their own academics after Oxford, Moscow University and MIT.

A second source of emphasis on contexts has come from the rise of an awareness of the social context in psychology and particularly the psychology of learning. A couple of generations ago, psychology textbooks were written as if their knowledge was equally valid everywhere. According to these, humans had the same moral development everywhere, had the same kind of reasoning everywhere, and perceived objects and ideas the same way everywhere.

Then, there took place a revolution in the discipline of psychology. Now it is believed that almost everything depends upon the context. Moral development relates to the local culture and social structure. There are no universal moral stages which everyone follows. How people reason is similarly shaped by the challenges they experience as well as the theories and concepts they have around them to guide them in their thoughts. Even how physical objects are perceived and manipulated is influenced by history and social structure.

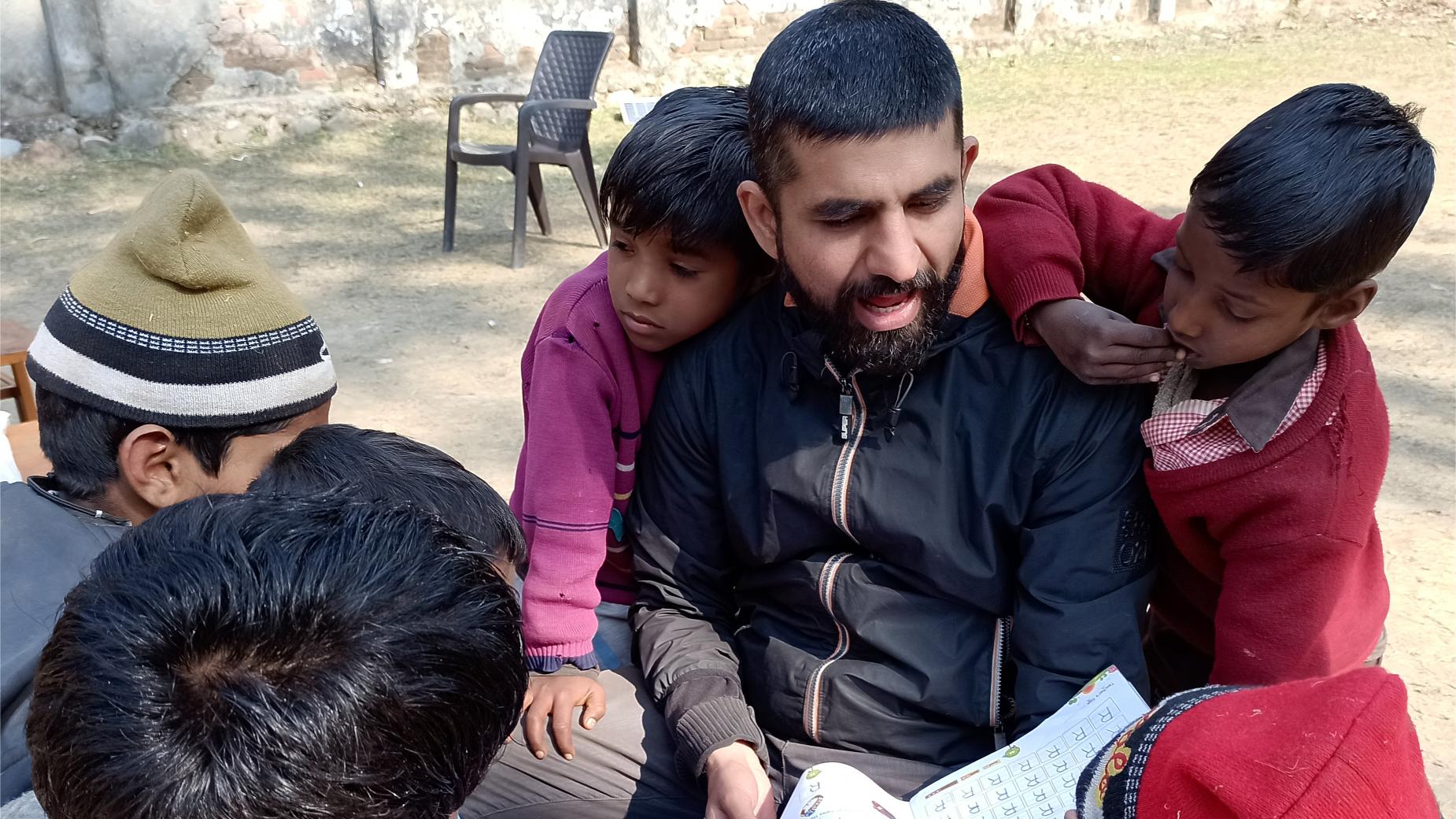

It has now become a truism in psychological perspectives on pedagogy that we must pay attention to the context of learning. Often this is indifferent to whether the aims of learning come from western or Indian or local culture. The emphasis is on connecting general theories to micro situations. For example, this may mean learning to connect a theory of caste with how it works in the local community, inquiring into its experiences and the symbols used by it. Such a position recommends that we try to solve a particular real-life problem so as to give a contextual grounding to all knowledge, whether universal or not.

A third trend which has influenced how we see contexts is the rise of post-structuralism, post-modernism and de-colonialism as trends in social theory. At the heart of all their different versions is a scepticism about the confidence with which European knowledges claimed to be the final truth. Why accept the sociological model of caste, in the first place, this will ask. This has gone alongside social and political movements which have pressed for other versions of the truth to be accepted. For instance, Dalit and feminist movements have argued that their perspectives are more correct than the dominant ideas of social reality.

Castes have been usually studied and taught from the point of view of the West or of the dominant castes. Feminists further say that the women’s perspective on caste was usually suppressed in what was taught in schools and universities.

There may be others who disagree with all of the above. They may insist that the Gita’s interpretation of caste had been suppressed and should be paid attention to. Like the anticolonial thinkers, many scholars today say that Western knowledge systems constitute just one particular way of seeing the world. We need to cultivate our own ways of seeing the world, they say.

However, this is not simple. The Dalit’s way of seeing the world may be different from that of the dominant caste. Some castes may see eggs as something they cannot bear to touch or keep in their shops. However other castes may consider them quite innocuous and a cheap, though bland, source of nutrition.

Women do see the world somewhat differently from men and so on. A Dalit man may think nothing of walking home alone at night. Women have learned that this exposes them to the dangers of being attacked. Which context should we give priority to and why?

Many philosophers have believed that we can somehow logically uncover a final moral wisdom, which transcends all different contexts. They believe that we can have an objective moral compass, which will show us the right direction in all contexts. However, many contemporary philosophers believe that even our moral reasoning rests ultimately on intuitions. These come from experiences. They can vary from person to person.

We can reason about many things. However, the ultimate foundations of moral knowledge do not rest upon a single solid stone. This does not mean that we give up on reason or on finding common grounds. Instead, it means that we pay more attention to dialogue. We must try to better understand where we and the other are coming from.

The general or the contextual? Teaching about casteism

The context is thus seen in different ways by different points of views. We can talk about them, even if we do not always agree. One important question here is whether we can ever learn or say or understand something which is not from our context.

For instance, can a non-Dalit take a stand against casteism? Can we teach about casteism to a classroom with children from mixed backgrounds? Let us use this to illustrate the relations between contexts, broader moral truths and dialogue.

Many social scientists and philosophers now believe that we always speak from a particular social location. We always have a context within which we have been formed and which has shaped our understanding, emotions and actions. We are never context free, we never see things with God’s eye, which can see everything, from every direction, at the same time.

However, we can still grow, our experiences are ever-changing. We can indeed learn to look at caste, gender, food, love and hatred from broader and different perspectives. We are not fixed. We are continually being recreated by our actions, our reflections and our environments. We never become context free. However, our contexts or social locations may expand and change. This leads to the development of more general knowledges. They may, in certain situations, be more valuable than particular knowledges.

As social processes like the market, state and rationalization bring more and more people together to rub shoulders with each other, they can develop affections which reach out across social boundaries. It is indeed possible for people from dominant castes to see others as people like themselves and to empathize with them.

They then start feeling horror and shame when they begin to understand what their friends may have gone through. This can lead people from dominant castes to introspect and to go through a painful process of changing more of their views and emotions. This is easier when the social circumstances change and become more expansive and inclusive so as to support such interactions and conversations. It is more difficult when social circumstances keep framing the others in negative ways.

In other words, when we remould contexts to expand people’s experiences and exposure, then they begin to change. They start moving to a more abstracted and inclusive moral position and renouncing casteism.

This is the challenge for the teachers who want to push against casteism. What experiences, theories, emotions can they place around children which will help them make the desired shift? Meanwhile, for the teachers themselves to find it easier to think and act in this direction, they need certain situations to be in place. The context becomes bigger, but never ceases to matter.

The context matters in the opposite direction too, taking up a smaller and local form. As many anthropologists and sociologists have noted, there is no single homogeneous caste system in India or the world. We cannot teach about caste in a general way and expect it to change all children everywhere in India.

The status symbols used by dominant castes are different in Punjab when compared with the status symbols in Maharashtra. In Patiala the dominant caste may celebrate a particular style of tying the turban, boisterousness and eating chicken with gusto. In Pune the dominant caste may consider a certain kind of kurta and dhoti its marker and behave with primness, turning its nose up against any kind of non-vegetarianism.

Changing casteism in Patiala will call for seeing these symbols for what they are. It will also call for a new attitude of restraint and rebuilding the emotional schema of celebrations. In Pune changing casteism may call for accepting non-vegetarianism and no longer recoiling with nausea over it. The particular ways in which casteism works are different in different places. The teacher has to respond to those contexts. They cannot just simply think that a general talk against casteism will do the job. Instead, the particular ways in which status, occupation and power work in that particular place will have to be slowly un-clawed and peeled back.

Children and youth will need to be scaffolded to discover a new and better way of seeing food, power, work, marriage and friendship. Otherwise, they will repeat the general theories of caste. However, they will still remain enmired in the particular way in which it works in their region.

The context, thus, has many dimensions. It may be our immediate world. But we cannot always go by what the immediate world says. The immediate world may recommend that we just carry on with older practices. The immediate world may also have contradictions, with students being pulled in support of and against casteism at the same time.

For too long we have thought of education only in the false universal model, with one particular group’s discourses masquerading as God’s eye. Reacting against that, now we are also in danger of seeing the local as God, somehow nobler and truer than all the other gods in the universe.

Perhaps the way forward is to build more dialogues between different kinds of understanding. There is a place for the more general and there is a place for the more local, indeed for multiple locals. By trying to understand each other, we may find a better way for them to co-inhabit this world.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!