Difficult topics in children’s literature: reflections from the field

Books on difficult topics like loss, caste, and gender help children reflect and question. This article shares field experiences, challenges, and strategies for sensitively engaging young readers in transformative conversations.

Book sessions with children never truly come to an end. They leave experiences behind. Threads of something a child has shared, something left unsaid, a quiet observation, or a telling drawing. These threads are stronger when the books shared with children are about themes that are not always discussed, such as loss, gender, loneliness, fear and hatred.

Even after years of conducting story sessions with children, it is still a conscious effort for some of us to choose books around difficult topics. Will this book overwhelm children? Will I be able to do justice to the thought and emotion of the book? Are my anxieties about this topic holding me back? The questions persist. While we might not offer definitive answers, some reflections and thoughts might help someone with the same questions.

Arriving at a theme/topic

Listening often leads us to a topic. The theme to be chosen emerges after being with children, talking to them a little, and listening to them for substantially longer periods of time. The topic is not often our choice, but an attunement we arrive at with children. It could stem from classroom dynamics or personal stories shared through drawings and narratives. Topics emerge from discussions around interesting events.

Photo credit: Palakneeti Khelghar

It would serve well to remember though that the book-reading if done with a purpose of bringing out a behavioural change or with the intent of a specific outcome, e.g., ‘to help someone forget their grief’, might not always work out. The reason that seems to work for choosing a topic is merely that children might want to talk about it.

Manasee remembers a reading of ‘Sadako and the thousand paper cranes’ emerging after a debate between a few 12-year-olds about whether every country should have a nuclear arsenal. A reading of ‘The brothers of Chichibaba’ happened when discussions in the classroom frequently started to linger around ‘us’ and ‘them’.

Choosing books – or letting them find you

It is our experience that books find us. A recommendation from a friend or a mentor whose taste in children’s literature we trust, a footnote in an article, or even recommendation from online e-commerce sites (which sometimes quite hit the mark!). Books that are in no hurry to give answers, those that ask questions we are not ready to answer, work quite well. Books such as ‘Sad book’ by Michael Rosen give the reader spaces for silence and even discomfort. Books that aren’t quick to paint a character in an expected colour, such as ‘Cry heart but never break’ by Glenn Ringtved, provide opportunities to navigate difficult things through different lenses. Having a collection of books on diverse, difficult themes has proven very handy when a theme emerges.

Photo credit: SAJAG

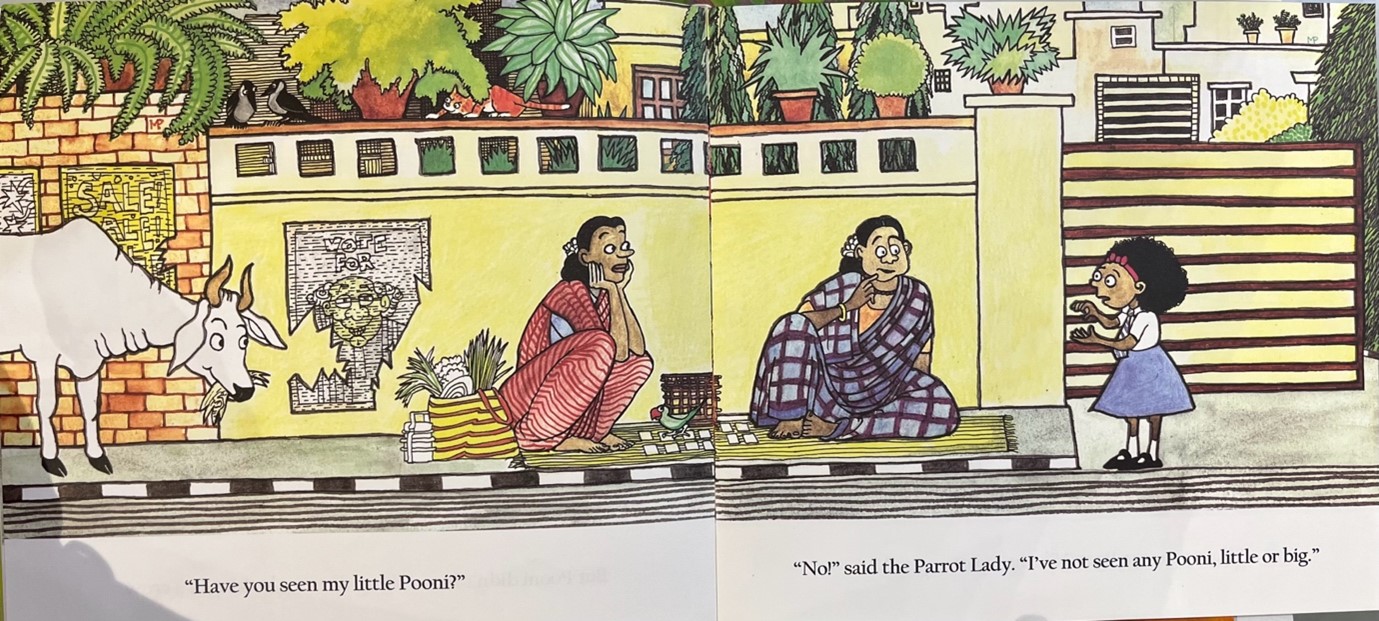

Perceiving that six-year-olds from different backgrounds in the class had a feeling of ‘us’ and ‘them’ reminded Sajitha of the book ‘My name is Gulab’ by Sagar Kolwankar. It is a story about a young girl, the daughter of a sewage cleaner, and how she is treated at school. When she read this book aloud to her students, it hit them hard. Through the story of a person who has experienced discrimination and can strongly voice her dissent, the thought that background should not matter, and that we are capable of being different, reached children much better than mere prescriptive words would have.

Before the reading

It is important to listen to how we meet the book before taking it to children. Can you talk honestly about the topic? Do you feel comfortable asking questions about the book? Do you feel OK to say that you do not know the answers? Are you capable of handling children’s responses to it? Will they feel hurt if you read this? More importantly, it is okay to be anxious before reading?

Coming from a privileged background, Sajitha was unsure if she was the right person to introduce the topic of caste. But this topic needed to be handled empathetically, and with an understanding that privilege can be ‘given’ and ‘earned’. With a clear objective that the reading focus would be on the behaviour of the characters in the book and the outcome, Sajitha decided to proceed with the read-aloud of this book.

Photo credit: Palakneeti Khelghar

Another helpful practice we have learnt is to leave tracks of our thinking in the book. Our inner voice speaks to us as we read. It often brings out experiences and connections that enhance the quality of our comprehension and connection. Small Post-it notes stuck in the pages help to track these thoughts. They often help to make the reading more personal. These also demonstrate our connection with the book.

While reading the book

Reading a book is always more than just the book. It is the shared moment, where the reader and the listeners both bring something to the reading. It is tempting to fall into the trap of following a scripted guideline for ‘How to conduct shared reading’, or ‘How to conduct a read-aloud’, which talks more about the technical aspects of the reading than the engagement of the child. However, experience says that what works best is the genuine interest of the reader to share the book with children. Sharing personal experiences related to the theme is an effective way of opening conversations and breaking the walls. The reader sharing their vulnerability helps children also feel safe in entering the space of the difficult theme.

It helps to elicit responses in multi-modal ways. Sometimes we draw. Sometimes we talk. Sometimes we create new stories. Sometimes we enact. Even if we decide to do nothing, the story still works quietly inside us.

A planned post-reading activity is useful. However, we need to be flexible and open to what the reading evokes. Children often engage in varied ways, some visible, some not. Hence, forcing a particular type of response might not always work for all. Even with planned activities, children always have the freedom of not participating and choosing their way of expression.

Why bring in difficult themes?

Our current education system often delays the introduction of complex social themes, such as caste, gender, and dignity of labor, until much later in a child’s schooling. However, qualities like sensitivity, open-mindedness, and ethical imagination begin forming in the early years. If we wish to nurture a socially conscious generation aware of issues related to equity, then we must engage children with these themes during their formative stages.

During the read-aloud session of ‘मुलींनाही हवी आझादी’ (‘Girls also want azadi’), written by Kamla Bhasin, and translated by Mukund Taksale, the text said, ‘झाडावर चढण्याची आझादी’ (‘I want the freedom to climb trees’). Some boys remarked, “They shouldn’t. They don’t know how. They’ll just cry.” One boy admitted, “I’m scared of climbing trees too. But my younger sister isn’t.” And then one girl said something that changed the tone of the conversation: “If we don’t know, can’t you help us?” That question made the boys stop and think. It felt like a natural place to pause the discussion.

Fortunately, many children’s publishers today, such as Muskaan, Tulika and Pratham, are intentionally creating books that address these difficult realities with honesty and care. But what matters just as much as what is introduced is how it is introduced. These stories need to be mediated by educators who are informed about the issues and are aware of their positions and biases. It is this conscious engagement that transforms a book from a story into a site of reflections and transformation.

We should bring such stories into our classrooms—not to impose answers, but to raise questions that linger and grow.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!