Picture books: bringing together the world and the word

This article discusses the critical role that picture books can play in nurturing children's engagements with reading the word and the world. It does this with examples drawn from a wide variety of picture books, and provides insights on the ways in which these can be used with children to further their development.

In the picture book Pishi and me, the central character is a child who loves to go on walks with his aunt. The world of the child comes alive in many ways in the book from the spaces the child occupies at that point in their life. The height of the child, for instance—looking up, looking down, looking at an angle—shows the manner children orient themselves in the direction of the person, object or view of the world that they are engaging with in that particular moment in time (Figure 01). The child points, identifies, relates and abstracts the world of daily experiences and relationships. In Freire’s terms, the child is ‘reading the world’ long before beginning to ‘read the word’. However, significant adults in a child’s life often restrict their understanding of reading to decoding and reading text. An expanded view of literacy and reading is essential to sensitively approach the question of a child learning to engage with text and the role picture books play in that context.

Picture books can play a critical role in bridging the visual world of the child. This is brilliantly captured by the illustrator in Pishi and me through symbolic representation in text. In this article, we will explore some strategies and features of picture books that support their role in bringing the world and the word together.

Reading expanded

In an insightful speech to a group of teachers, the Swiss literacy researcher, Denise Von Stockar presented an accessible view of reading. The core of the arguments were the multiple angles in which the act of reading involves the world of the child. Reading is listening. The child listens to lullabies, songs and stories, much before they begin reading text. Introduction to language happens at a very early stage, as opposed to familiarity with print and script. Reading is seeing. The child can visually process the world, recognize shapes and forms, orient and point to familiar objects, corners and people, much before they begin reading text. Reading is speaking. The child learns at a very early age to recognize and associate specific sounds with specific features of the world around them. In this process, the child learns the existence of discrete words, each of which are abstract yet specific associations of objects and sounds.

This is when a child can be introduced to board books which have durable pages and bold images with a focus point in each page. The child can recognize and point to familiar features in the book or prompt the adult, as only a child can do, to provide the appropriate sound associations for the visual cues in the book. The tactile experience of holding a book, turning the pages, sometimes even chewing on the book, and throwing it around, makes engagement with the book a multimodal experience.

As the child grows older, they also learn to express internal states of being and emotion in their simplest word forms. Older children are also able to share narratives in speech and can share stories of their own imagination. Picture books with simple/linear or complex narratives, with or without words, can be introduced to children to familiarize them with the book’s orientation, its pictures, and the directionality of print (which is different depending on the language), even if they are not yet familiar with the myriad complexities surrounding decoding the symbolic richness in script. However, the engagement with picture books is not only related to reading the script but also to the child expressing internal states of meaning-making and emotional landscapes while narrating the sequence of images. Picture books are rich sources of narrative building with complex, multiple layers of storytelling happening in the images themselves, which a child can decode without decoding the script also present in the page.

Reading is writing. The earliest forms of expression other than speech are often scribbles and doodles that a child makes on sand, mud and paper using various available instruments, ranging from sticks to pencils to crayons. This is not the script used to symbolize individual alphasyllables or logographs or words, but more whole worlds of visual storytelling that bring in world building or narrative drama all at once.

In a print-rich environment with many easily accessible picture books, whether at home or in early preschools or later in schools, rooms and libraries rich in picture books can play a significant role in encouraging emergent literacy. Here the availability of print in the environment orients the child to develop familiarity with the format of printed books, the conventions around orienting, and reading narratives in pictures. This then helps to lead them inevitably, inexorably toward script-specific concepts of words and their symbolic subunits, most familiarly alphabets in the Indian context.

Picture books expanded

Children actively engage with their world and explore picture books as they do the rest of the world. How do picture books lend themselves to rich exploration by children?

Picture books written for children have a storied history, which dates to the late 18th and early 19th centuries in Europe. These evolved and morphed into currently recognizable forms by the early 20th century. Early books were mostly pop-up or similar novelty books, or illustrated books with images supporting the text. The picture books of today are defined by the equal and often divided partnership between text and illustration in parallel storytelling. The blend between text and image creates a magical world that presents itself in simple or complex, and often deep, ways where children find their way around discovering new corners or finding familiar spots. The idea of picture books acting as ‘windows’, ‘mirrors’ and ‘sliding doors’ is not a new one.

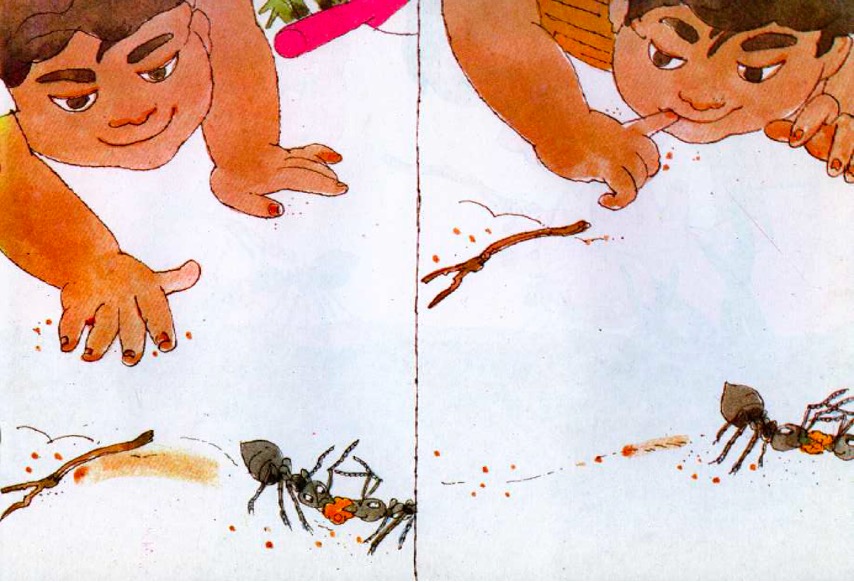

How do these opportunities for windows and mirrors, which offer us glimpses of the world-building in the child, get reflected in the form of the picture book? As discussed in the example that opened this article, Pishi and me, a child is often the central character in a picture book, with illustrations often presenting the story from the child’s perspective. Another excellent example is the boy observing ants in Busy ants by Pulak Biswas (Figure 02).

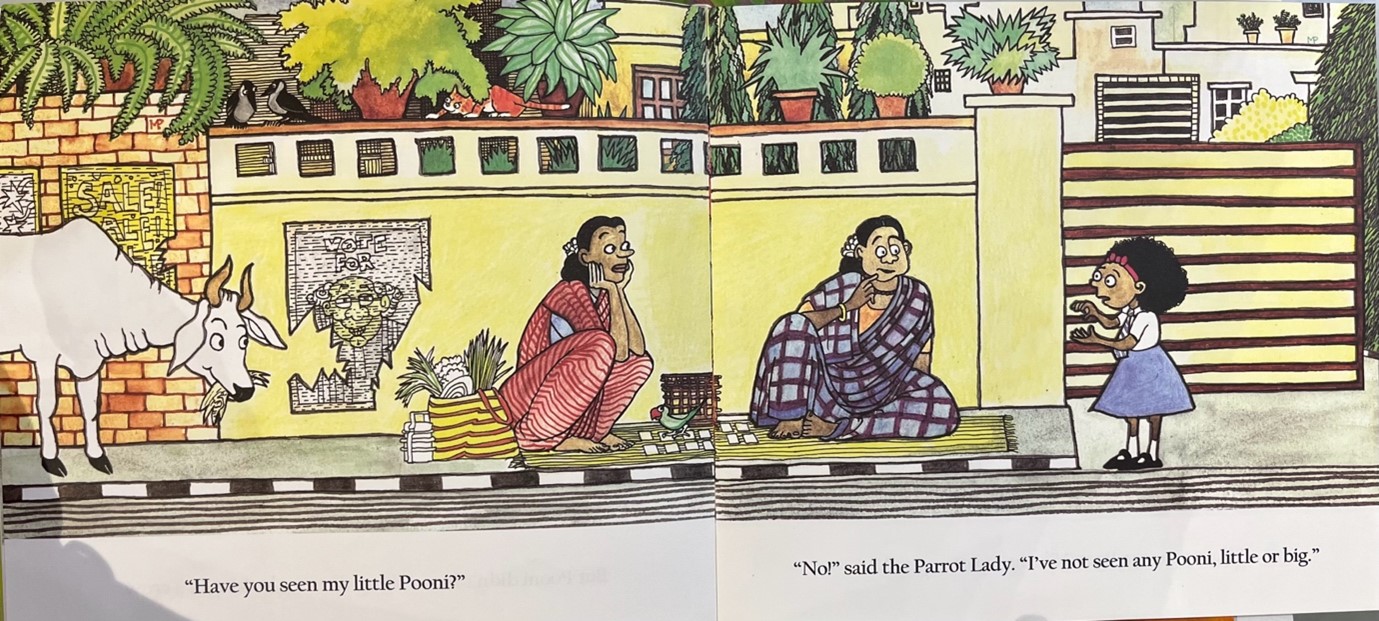

However, the child need not be the focus of the perspective, and can occupy other frames of action, as in Where’s that cat? by Manjula Padmanabhan. Here, the moving autorickshaw guides the reader through the narrative frame in the illustration. The rabbit’s movements perform a similar function in Eric Rohmann’s The flight of the rabbit.

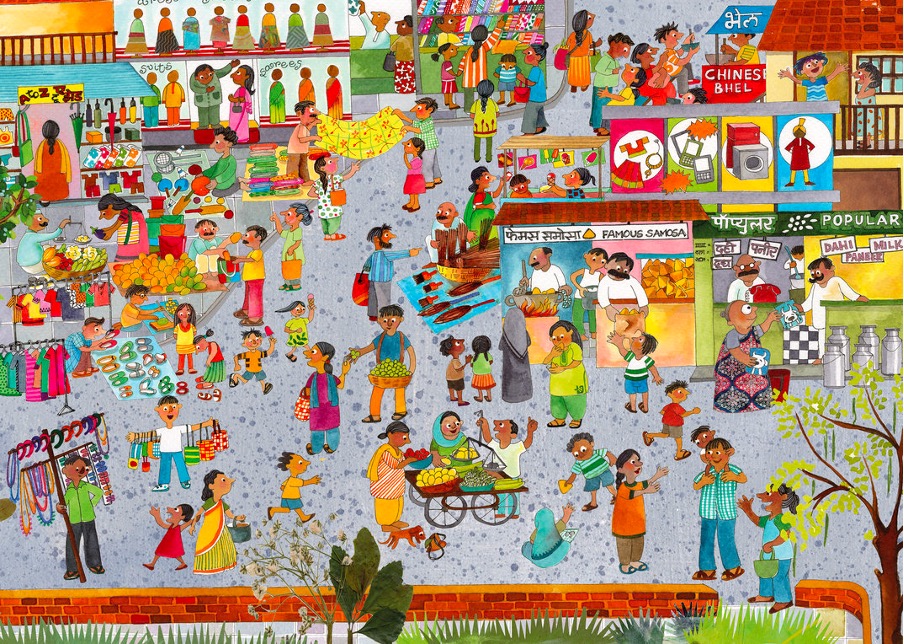

Sometimes, pages densely populated with illustrations, for instance, intended to show a diverse city in Deepa Balsavar’s Nani’s walk to the park, can be navigated with a clearly identifiable character such as the grandmother in a distinctive Ajrakh sari in each page guiding movement across the page (Figure 03). These devices help in drawing the child’s attention across the page and to the next, carrying the story forward.

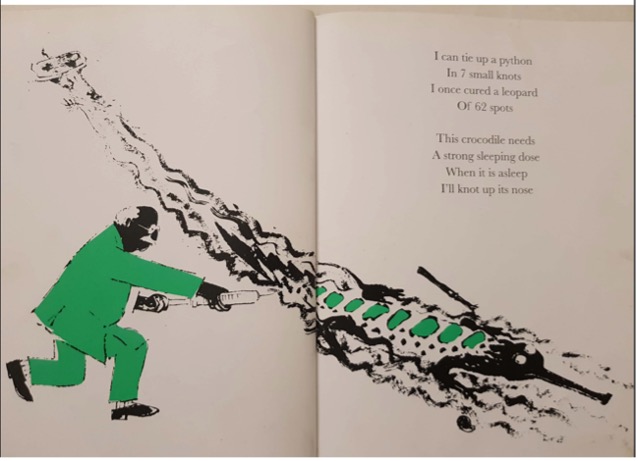

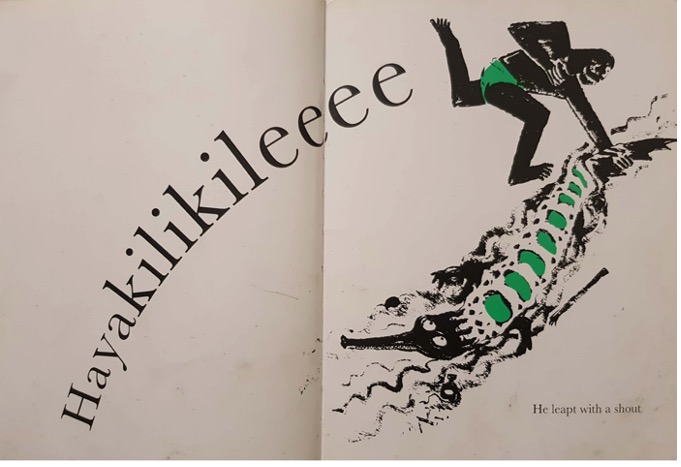

Humor in the form of slapstick action often finds a space for engagement in picture books. Anushka Ravishankar’s Catch that crocodile is a good example. This classic, illustrated by Pulak Biswas, plays with the placement, size and movement of the text along with incongruous movements by characters, and outsized objects like giant syringes. It is visually rich, with cinematic action sequences (Figure 04). Ashok Rajagopalan’s Gajapati Kupapati series is a great favorite with children. This is often due to the extra dose of action experienced by the central character, an elephant. Animal characters figure significantly in many picture books.

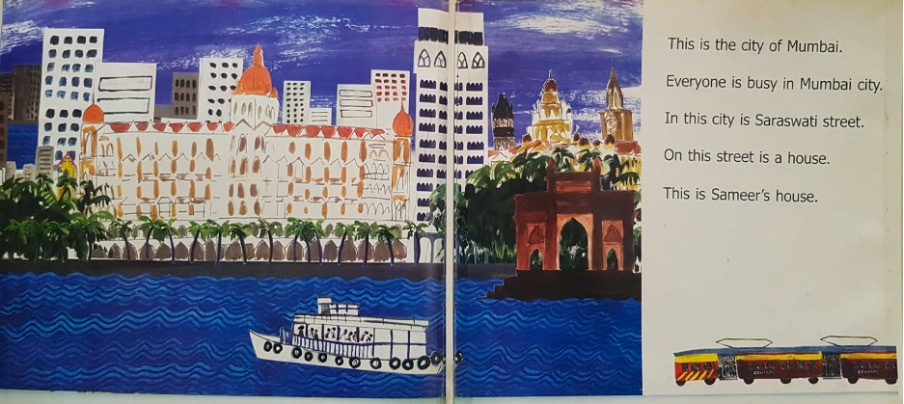

A steady pace in the story generated through momentum is important in sustaining engagement from the child. Text can also be used effectively in this case. Sameer’s house uses repetitive, cumulative, pyramid-like build-up of text in each successive page. This allows for excellent engagement in activities such as reading aloud, as children would get in to repeating familiar text that builds up rhythmically and systematically (Figure 05). This clever design in the book uses the potential for such repetition to reinforce ideas on scale in geography and astronomy. A placeholder of Sameer’s house is also used to indicate location in the illustrations, as the scale of space grows larger with progressive pages. A similar pattern can be seen in several books including The sea in a bucket.

The examples suggested earlier appear to focus on entertaining characters or storylines, or clever design principles. However, engagement through effective storytelling can bring in further emotional connection, self-reflection (‘mirror’) and new learning (‘window’). A book can be a window for some, a mirror for others, and a mix of both for some. This depends on the individual contexts, and the children’s conditioning. A girl child from the Bakarwal community may find fictional Sadiq’s desire to stitch in Sadiq wants to stitch as a relatable tale, while a boy from the same community might find it a new experience. A child from a community from a different geography, in which stitching is a part of its everyday life, might find Sadiq’s story both a mirror to their way of life, and a window to a new community and landscape.

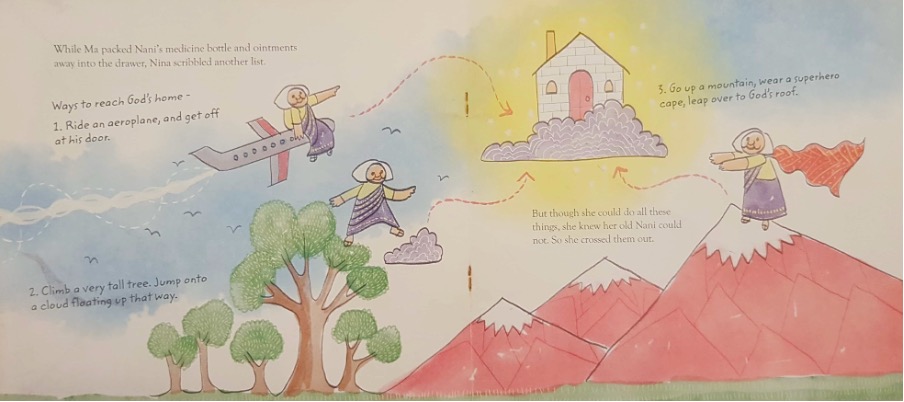

Picture books hold death, loss, gender and disability easily among their pages in a manner that children can relate to, as they encounter these facts of life and living. Gone grandmother by Chatura Rao and Krishna Bala Shenoi, explores a child’s meaning-making process of losing her grandparent in a gentle, humorous manner. At the same, it locates this firmly in the child’s world, as shown by the ideas that spring out of her in the illustrations (Figure 06).

Allen Say’s Emma’s rug explores a child’s deep attachment to the objects in their world, and the impact of loss on their emotional engagement with it. The picture book’s illustrations find a way to convincingly convey Emma’s emotions. Raviraj Shetty and Deepa Balsavar’s Our library16 finds a welcoming space for a diverse group of disabled children within a library, where there is a careful attempt in depicting disability with accuracy, care and love.

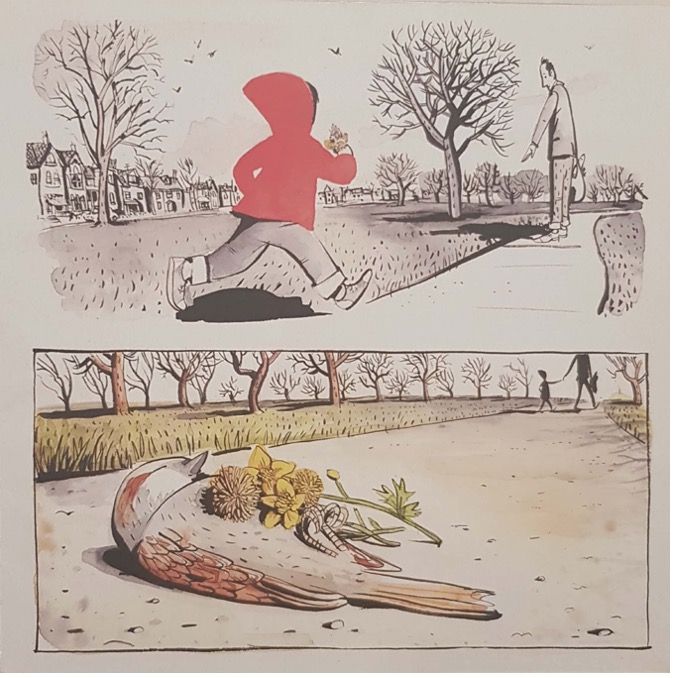

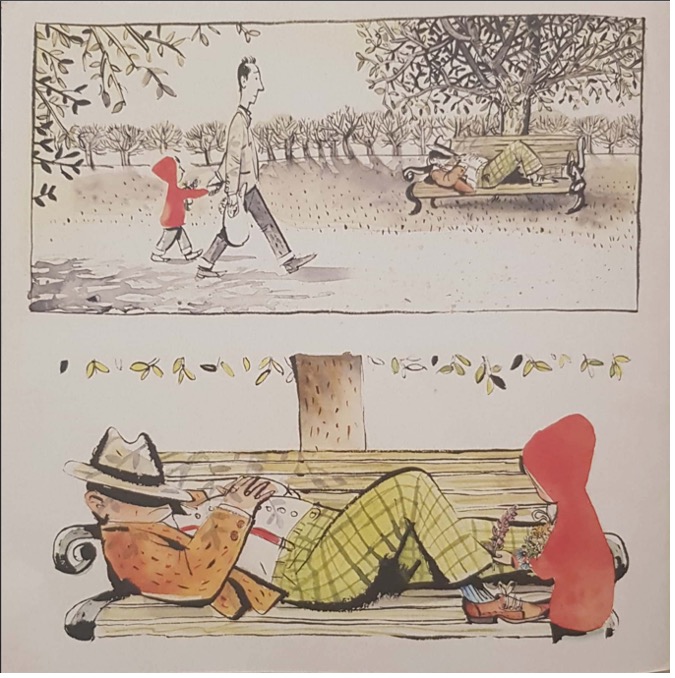

Wordless picture books always find a special place in children’s libraries as they pave the way to open fantasy and reality alike, in ways that text could sometimes constrain. Footpath flowers has a young child who goes on a walk with the parent, gathers flowers, and shares love with everyone she connects with in the walk (Figure 07). Aaron Becker’s fantasy Journey has two children embark on an adventure in a world created and powered by a red crayon. In each of these cases, the storytelling is entirely done by illustrations, but there is an underlying script that keeps the story going, which a child can tap as the cleverly designed books guide them in linear and non-linear ways to old haunts and new crannies.

Reading journeys as a cultural enterprise

Readers are not created in a world filled only with books. Readers are nurtured by communities of other readers. Significant adults such as grandparents, parents, uncles and aunts, older siblings and cousins, tell stories and sing lullabies when children are young. Other adults, more of the above, educators in classrooms and libraries, and other mentors, are important in different stages of the child’s life. They can all play a role in bringing picture books to children.

Picture books are designed to engage the child in the act of reading in complex ways. Therefore, the adults in their life can help in curation, reading aloud, reading together, gamification, sharing their responses and thoughts, asking questions, and offering a space to listen to responses to books, reading and meaning-making around books. For several children, picture books can act as a refuge from the complexities of the world. A caring adult who shares the joy of reading can always make the refuge less confusing and more accepting with their presence. Communities of readers grow as many young readers experience their individual reading journeys into adulthood, ready to nurture the next generation of readers to bring them to picture books and other books as they grow older.

In India, we must address the question of creating communities of readers. This is crucial, as reading for pleasure or meaning-making, either individually or with adults, is not a culturally widespread activity. This is the case due to complex historical and sociological reasons. Access to books for a vast population continues to be limited, even as the number, diversity and quality of picture books is slowly growing across the country. Also, picture books are often expensive. While efforts have been in place for several years to reduce the price of books, parents do not easily buy them for children even when priced low. A wide network of libraries across the country with spaces and collections for children can fill this gap. Such a network can also provide spaces and programs for making reading for pleasure, learning, and life skills a cultural enterprise that can hope to reach all children.

Are picture books the future?

Picture books are for all ages. Adults and children alike enjoy them. In this article, we briefly forayed into the many ways of children reading the world and the word through the picture book. However, we live in an increasingly digital world. Screen time now increasingly occupies significantly more time in young children’s lives, with hassled adults handing over cell phones to calm children down. Online video sharing platforms have penetrated remote parts of the country on hand-held devices, even before the first picture books have reached them. In such a scenario, what is the future of picture books?

Creators of picture books are essentially storytellers, so long as there are creators for this basic human trait, there will be picture books. So long as people participate in economic activities around sustaining the creation of picture books, they will continue to exist. So long as there are communities of readers who love and nurture reading, picture books will continue to be read and be around.

And so long as human beings engage with the physical world around them and value reading the word, we will find a space for picture books in their lives. In an increasingly digital world, communities of readers are coming together around physical and mobile libraries. Picture books continue to weave their magic in bringing up children to relate and process the complexities of the world around them and far away.

References

Balsavar, Deepa. Nani’s walk to the park. Bengaluru: Pratham Books, 2018.

Balsavar, Deepa, and Priti Rajwade. The sea in a bucket. Bhopal: Eklavya, 2013.

Balsavar, Deepa, Deepa Hari, and Nina Sabnani. Sameer’s house. Chennai: Tulika Books, 2006.

Becker, Aaron. Journey. Somerville, MA: Candlewick Press, 2013.

Bishop, Rudine S. “Windows, mirrors and sliding glass doors.” In Collected perspectives: choosing and using books for the classroom, edited by Leslie Prosak-Beres et al., 1–5. Boston: Christopher-Gordon Publishers, 1990.

Biswas, Pulak. Busy ants. New Delhi: National Book Trust, 1987.

Freire, Paulo, and Donaldo Macedo. “The importance of the act of reading.” In Literacy: reading the word and the world, edited by Paulo Freire and Donaldo Macedo, 5–11. London: Routledge, 1987.

Gupta, Timira, and Rajiv Eipe. Pishi and me. Bengaluru: Pratham Books, 2018.

Lawson, Joarno, and Sydney Smith. Footpath flowers. London: Walker Books, 2016.

Nainy, Mamta, and Niloufer Wadia. Sadiq wants to stitch. Chennai: Karadi Tales, 2020.

Padmanabhan, Manjula. Where’s that cat? Chennai: Tulika Books, 2009.

Rajagopalan, Ashok. Gajapati Kulapati. Chennai: Tulika Books, 2010.

Ravishankar, Anushka, and Pulak Biswas. Catch that crocodile! Chennai: Tara Books, 1999.

Rohmann, Eric. My friend rabbit. New York: Roaring Brook Press, 2002.

Rao, Chatura, and Krishna Bala Shenoi. Gone grandmother. Chennai: Tulika Books, 2016.

Say, Allen. Emma’s rug. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1996.

Shetty, Raviraj, and Deepa Balsavar. Our library. Bengaluru: Pratham Books, 2023.

Von Stockar, Denise. “The importance of literacy and books in children’s development: intellectual, affective and social dimensions.” 2006. Accessed September 2, 2025.

Note: A version of this article was published in the magazine ‘Teacher Plus’ in June 2024.

No approved comments yet. Be the first to comment!